Informed by their theories, Wright ultimately attempted to bind together these forces- education, machines, architecture, and democracy-when he founded the Taliesin Fellowship in the 1930s.

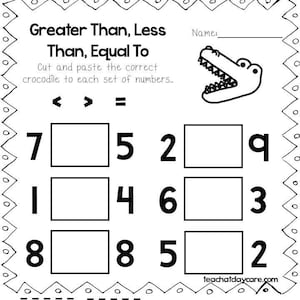

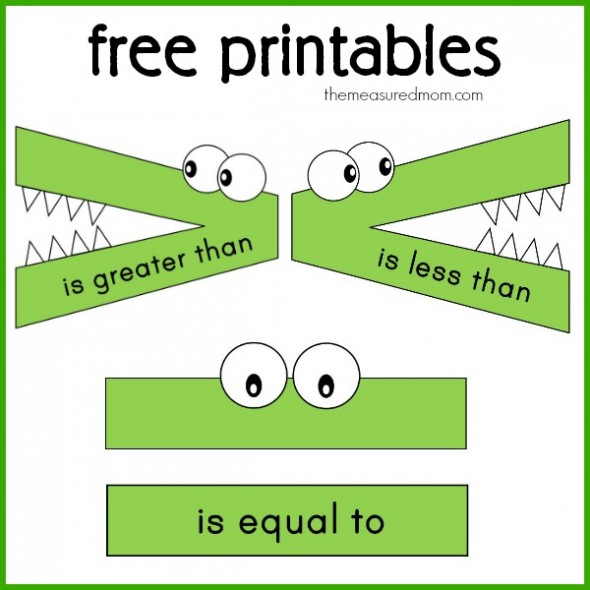

#Greater than less than equal to art craft manual#

Wright laments, towards the end of his essay, that education in America has not forged connections yet between “Science and Art” or adopted curriculums of “nature-study.” However progressive educators, such as John Dewey, who founded the experimental Laboratory School at the University of Chicago in 1896, and Wright’s own aunts, Jane and Ellen Lloyd Jones, founders of Hillside Home School in 1886, were in fact advancing new pedagogical models centered on active learning from experience and on unifying practical or manual training with intellectual pursuit. Wright embraces the machine, broadly speaking, as capable of reducing human labor and expanding lives and “thereby the basis of the Democracy upon which we insist.” From the standpoint of architecture, the machine reduces waste and lowers costs so that “the poor as well as the rich may enjoy to-day the beautiful surface treatments of clean, strong forms.” Indeed throughout his career Wright would experiment with various ways to harness the advantages of machine production to design quality, affordable housing for large numbers of people. While any individual book may appear ephemeral or fragile, the sheer number of them, the number of people reading them, and the ability to reprint them renders “printed thought … imperishable … indestructible.” Widespread literacy and access to knowledge ultimately contributed to the democratic revolutions of the eighteenth century, including the American Revolution.

Before the age of Gutenberg, architecture centered on the handicrafts and was the “universal writing of humanity.” The invention of the printing press-arguably the first great machine, Wright points out- transformed architecture but also social relations. Calling the machine “the great forerunner of democracy,” Wright invokes an argument advanced by the French author Victor Hugo in Notre-Dame de Paris in 1831 that reflects on the power of the printed word. The themes Wright outlined in his talk would preoccupy him throughout his life, namely the relationship between machines, education, architecture, and democracy. In 1901 Frank Lloyd Wright delivered a seminal address called “The Art and Craft of the Machine” to an audience at Hull House, an organization that offered social services, such as education, childcare, and legal aid, to poor communities in Chicago.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)